9/13/2001

These towers are gone. I haven't exactly seen that in a viscerally convincing way, though I can see a lot of smoke, a lot even now. I did stand and watch them for some time while they poured smoke out of the rents left by the planes. By the time the first one fell I was on my way home, on foot--a long way, from 46th Street to 180th. I had no idea they'd just fallen. My head was full of the vision of them wounded, and that was already too much to think about.

It's not that one has trouble believing it, exactly. That's what we all say, anyway, and I don't know that I can express it any better. But of course we believe it. After a few unrelated people tell you an event has taken place, there's not much doubt, and anyway everyone saw it on film--most of you ouside the city have probably seen a lot more of it than I have, and I got to watch it with my own eyes for a while.

Maybe when we talk about not believing we just mean we haven't sorted through all the ramifications yet. Today I went upstairs again, to try and find Tom Irvin and Bob Higgins, people I worked with when I first came here, who were scheduled to be in the worst possible place that morning--the hundredth floor of 1 World Trade, the western tower--more or less exactly where the first plane hit. While I was up there I looked south, of course, and there's still a plume of smoke down there after two days, but it's white smoke now, and much less than there was originally. You can see, of course, that they're gone. Smoke or no smoke it's entirely clear that you'd be able to see them if they were there. But when the smoke settles, when a few weeks have gone by and I look down there and see Staten Island sloping up out of that deep blue water behind a modest skyline, maybe that will feel like belief.

I first came to New York in July 1998. My brother Jon, a Manhattanite for some six or seven years already, had urged me to come months sooner than I'd planned, and he orchestrated the whole thing for me; within a day of my arrival I had a room in a huge uptown apartment with some people he knew, a small tech-writing project he passed off to me and an appointment with a temp agent who'd never yet failed to hook anyone he knew up with work the following day. Oh, and he gave me an entire computer as an early birthday present--not cutting-edge or anything, but it was nevertheless sort of my first contemporary machine, replacing the SE30 I'd been using, which was also a gift from Jon. It was fairly clear through the whole process, actually, that he chiefly wanted me to come to the city so I could play networked computer games with him.

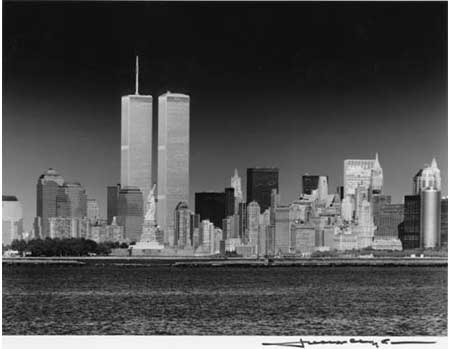

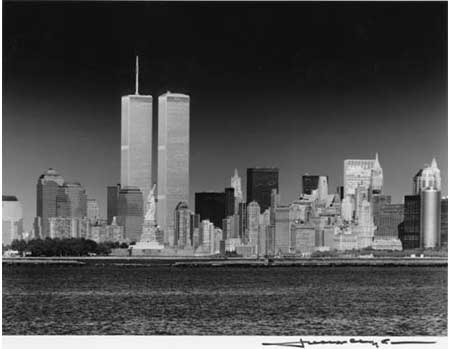

Soon I was tidily squared away in my new urban lifestyle. It was wonderfully dramatic; from the bedroom window I could see the lights on the George Washington Bridge, and from my desk at the temp job in midtown I had a glorious view south: the Empire State building on the left, very close by, the Twin Towers directly in front, and off to the right the Statue of Liberty, so oddly small next to the skyline; then New York Harbor, a really striking color on clear days in autumn.

I never really had the experience one expects as a temp. I got into that first job without any particular project lined up for me, and before long it became clear that nobody in the office would ever take the initiative and replace me with a permanent employee, or not any time soon. In the end I worked there for just over a year, and even then I left of my own volition, tempted by a friend into chasing dot-coms.

After a couple of dubious years trying to establish a geek career, I've spent about a month now temping again while I try to decide what's next. To spend as little time as possible unemployed I went back to the same agent I was referred to three years ago, and she packed me right back the same building, of all things. So here I am again. 1166 Avenue of the Americas. 9th floor now, not the 37th where I was before; I don't have the view I used to have. I've been here for three or four weeks.

Two days ago I got into work a little late, maybe 9:05AM. Within a few minutes I was overhearing that a plane had hit the world trade center. (I was thinking of a little single-engine Cessna. Sometimes I'm honestly stunned by how pedestrian my imagination can be.) Spooked as everybody was, I started edging toward the elevator, wanting to go upstairs and see it for myself. When one of my bosses came back from doing just that and choked out "you can't believe how bad it is," I stopped hesitating and went. In the lobby somebody was loudly announcing that two planes had hit, which I dismissed out of hand; I still hadn't thought of anything other than an accident, and the odds of two at once are of course negligibly small. On the way up--it's a longish ride in an elevator--people were talking about the different sorts of planes they'd heard about, and one man said with confidence that the radio was talking about big passenger planes. Only then did I begin to think of it as an attack.

It's been a little haunting to remember just how much time I used to spend, at that desk on the 37th floor, imagining an explosion from one of those towers; how I would be the first to realize what it meant, and I would leap to my feet cursing or crying or whatever while the other people around figured out what was happening and glued themselves to the windows to watch the show. I tried to imagine how loud it would be. Wondered whether I'd be able to do anything useful anyway. One way and another I spent an inordinate amount of time picturing that one thing, that one wildly implausible and overly cinematic fantasy. It was really pretty typical of my thinking anyway; my imagination is generally both lurid and paranoid and since I was a kid I've been spending massive mental resources on tactics for reclaiming hijacked planes, subduing muggers, escaping volcanoes, and so forth ad nauseum.

In retrospect, though, it seems reasonably clear that this particular sequence ran through my mind as often as it did in part because some part of me kept looking out the window and thinking those are vulnerable. After 1993 you'd think we'd all be well aware of that anyway, but we didn't believe it. I still don't know exactly what I mean by "believe" in this instance but this time it matters that we didn't.

Yesterday I walked with Miriam and Rebecca from one place to another in town, trying to find a place where volunteer help was needed. It wasn't; it's almost surreal how thoroughly all the bases seem to be covered already. Blood donors were lined up for six hours, and all the common types were full to capacity by yesterday afternoon. The TV news was saying clothing was well stocked and no longer wanted, and the army of emergency personnel is apparently being catered by professionals or something; all anybody wants on a volunteer basis is money, which is what I really don't have to give.

Once we were convinced we couldn't make ourselves useful, we went home--which, these days, is a couple of blocks away from the GW Bridge. We walked out on the bridge on the way, looked down along the island; there was always a sweeping view of Manhattan from there. Yesterday there was just a great haze of smoke down on the southern end, and nothing much else to be seen. We stood and looked for a while, and talked about the trying to believe, and the meaning of it. To Rebecca it seems the WTC was always an emblem the worst part of the city, a symbol of arrogance. She said it actually wasn't bad at all to see New York looking more or less like any other city. The skyline looks stricken this way, I said; it may always look small and cowering without them.

"My eyes don't see that," she said. "But I guess you're probably right."

I tried for a while to look at it her way. Tried to picture the WTC as a corporate monstrosity looming over the rest of the city, sort of unnaturally; it always was incongruous after all. I looked at the Empire State, now the highest point in the city all over again--having decades ago weathered its own airplane collision and remained standing--so that all of Manhattan reaches its peak with that one spire in the middle of the skyline. It's symmetrical, a much more old-fashioned sort of a skyline that way, without those thick dark avant-garde bars of color all the way at one end of the picture. The skyline of Manhattan is still massive, remarkable just for its breadth in comparison to those cities with one tight cluster apiece of tall buildings that each calls downtown. And there is something reassuring about seeing the rest of the skyscrapers still in place. We are still New York without them, they stand saying. We always were New York.

It's not the first time I've thought such things in the last few days; the low stone walls of Central Park are as quintessentially Manhattan as they ever were. Even the idea of a disaster on the epic scale has a certain New York flair to it, and thank God the relief efforts clicked with New York alacrity. And the view from the bridge was unmistakably a New York view. Except that downtown is on fire, and the Towers are gone.

At least this much is certainly true, or will be when the smoke stops: you can see a little more sky now.

I went up to 37 once since I've been working here again, but I only saw a few people, and some of the others gave me queer looks when I appeared on Tuesday to see the damage. Why should they be expected to deal with the horror of a disaster they could plainly see but couldn't influence, and simultaneously greet an unexpected old acquaintance? I just nodded at anybody who noticed me, offered a grim handshake if they threatened to be effusive, and kept my head pointed out the window.

And it was truly incredible. I can describe it, but you've most likely seen much more detailed views on TV than the one I saw. Honestly I remember some of the TV shots more vividly than I remember the view I stood staring at with my own eyes. That, I remember more like a written description--as a catalog of particulars. On the right, the western tower--that's the one with the antenna--stood shattered and gutted around its top, with maybe fifteen or twenty floors above the hole settled loosely on one another, their windows gone, the roof sagging northward precariously. The damage from the plane was largely on the northern face, a gaping hole twenty stories high or more, smoke billowing out of it. Below that the building looked intact and normal. The other tower had a glaring firelit gash across most of the width of it around halfway up, but seemed otherwise undamaged below and above, up to the point where it was engulfed in the smoke from the first hit. The smoke was thick and black and floated up and east, out over Brooklyn.

My only point in saying the building looked undamaged apart from the impact areas themselves is that it honestly didn't strike me at all that they were in danger as a whole. I did think the top of the western one looked awfully unsteady, and when I overheard something a little later on my walk home I assumed it must indeed have slipped off. But I never suspected each floor in turn would give way under it when it lost its hold. And to find out the other went first, and toppled over to the side, as I understand--that was really unexpected. I thought a lot about how long it would take to repair the damage, and it even came into my mind at one point, as I stood watching the ravaged structure flickering, that the damage on the top on the western tower might be more than anyone would bother to repair. But that was the worst I imagined.

I stood watching for less than half an hour, getting as much of the story as I could from Felix Mateo, a sharp and personable former co-worker of about my own age. He and some others had seen the second plane coming in some twenty minutes before I arrived. Yesterday I saw some clips of that impact on TV, and it is absolutely staggering to watch. And then, slowly realizing that an attack was under way, and that nobody could really say how far it would go or how many targets there were, I began to feel unsafe in such proximity to the Empire State.

So I went back down, called Miriam, made some efforts to reach Jon or my parents--which was impossible--and left. It took a long time to get home. When I did get there, almost immediately I suggested to the girls that they go out on the bridge and have a look at the damage. It felt important to see it, for reasons I wasn't bothering to examine. But they told me then that the towers were gone entirely.

Yesterday we dropped by my brother's place for a while, though he wasn't in, to watch TV. Still no clips of the first building falling, and far too many speeches by politicians, but there were a lot more shots of people running in the streets, of the dust covering everything, and of the wreckage as it is now. Strange to see; over everything is a layer of loose papers, practically undamaged--perhaps the thing of which the buildings were most full, and certainly the slowest to fall to earth.

But they were beautiful. They made the skyline. They were the only part that was really hard to believe even when you were looking at it; they were the inspiring thing, the thing that made you glad such a place existed in your world somewhere. They seemed immune to perspective: anywhere you might be, in or around the city, you could see them, even though every other structure passed in and out of view as you traveled. And from everywhere they seemed to be the same size.

I will never get that photo now, the one I've been waiting for since last October, when on a clear night I stood on the elevated train platform in Astoria, the last stop on the N line, close by where I lived at the time. On a clear night in the fall the sun set right behind the skyline from there, and it was one of the warmest and most glorious sights I have yet seen.

On days out with my brother, if we happened anywhere so far south on the island, we would generally wind up at the top of Battery Park, between the World Financial Center and the water. There is a small walled marina, generally host to half a dozen of the most obscenely opulent yachts you can imagine a single person to own. We sat on the end of the wall, watching boats pulling in and out, daydreaming about having one of them to play with; above all we were just brooding on the money. Half the boats had contingents of jet-skis on board; one frequently seen boat had a little helicopter on an elevated pad. The World Financial Center sits right next to the WTC; we sat almost directly under the Towers, and looking up at them made us dizzy like children, and we watched huge gulls wheeling high above them, barely visible. It's exhilarating to see such a big thing, to know that people can make such things if they just want to. And it's strange to feel so small in the face of something your own species made.

Only this past Spring did I make it up inside the WTC, to the roof, on the eastern tower, with my younger sister and some other friends. The sun set as we were at the top, and in a punishing wind we stood a little while on the roof, looking down at the five boroughs as they mapped themselves in streetlights.

"Big," my sister spat, gesticulating, not even trying to make a sentence of it. New York was huge; it stretched astonishingly far around us. It felt like the map of an entire country. But the towers, I remember thinking, seemed disappointingly small from the top; it was odd to think I might so readily run from one corner to the opposite corner in a few seconds. The other tower, with its antenna taller than a lot of buildings, seemed not so far away, and not so terribly stout after all. These? These were the behemoths that could be seen from sea level halfway down the length of New Jersey?

But of course they were. After all we could see that far from where we were standing.

I don't really know where I'm going with all of this, as you can tell. I don't want to sit recounting every single thing that's happened in the last three days, or anyway I don't wholeheartedly want to. I've spent a hell of a lot of time walking up and down the island. I've spent a lot of time on the phone. Nobody I know has died, to my current knowledge, though some would have if they hadn't been running late; Tom Irvin told me today that he got out of the train in time to hear the first explosion, and took off running fast enough to see the second one from City Hall. We've made our apartment available to people we know who got stranded on Manhattan, or who might be sitting alone. Stories are traded. Sirens are constant. Nobody's looting, despite one ugly joke I heard on my way through Harlem. News trickles in. People are quiet, but nobody can stay morose all day, and certainly the whole city would never have done that.

Here's the thing, I guess. I've been enjoying being a New Yorker, even as I've been torn between the ease of staying and my deep urge to move somewhere much smaller. I've enjoyed living in the thick of legend, and I'm especially pleased to be in Manhattan again. And I have come to love the first sight of that skyline, from the train or the highway, that dark immense thing that is my home now, like the last corner you turn before you pull into your own driveway--my sign that I'm almost home.

I don't think it can be that any more. It probably won't change my schedule--I figure to be here another two or three years regardless--but I think passing this new empty skyline will always be a reminder to me that I can't be in New York as I know it again. This is when I begin to count down to my escape to a smaller city somewhere. From now on I don't really belong here any more.